Welcome to our website!

Drums Unlimited Rentals has been servicing the Washington DC area non-stop since 1962. Please be aware that we are not a retail store and we do not rent directly to the general public. We provide Backline, Instruments, and other hard to find specialty items to: Businesses, Organizations, and Churches. Local delivery available and we ship Worldwide!

Take a trip down Memory Lane

While looking for the words to write to give you a feel of the man who started all this, I happened upon an article written in 1994 by Dave Nuttycombe for the Washington City Paper. He used to work at Drums Unlimited back towards the beginning of it all, and I think his original article, which is posted below, is good insite on "Mickey" and how Drums Unlimited got started, and evolved. Thank you Dave Nuttycombe, and I hope you are above that $1.35 an hour now!

Bang the Drum Profitably

By: Dave Nuttycombe

It’s been 32 years since Frank “Mickey” Toperzer hung the small sign over the door of his shop on St. Elmo Avenue in Bethesda. For any business to last three decades is a feat; it’s especially remarkable for one with as narrow a product line as Toperzer’s. The blue-on-white letters on his modest marquee read “Drums Unlimited.”

Perhaps the “Unlimited” part of the sign explains it best. The wee retail

store is but the tip of the drumstick in an almost sprawling empire that includes a rehearsal space, a mail

order and instrument manufacturing business, and a musical-equipment rental service.

Perhaps the “Unlimited” part of the sign explains it best. The wee retail

store is but the tip of the drumstick in an almost sprawling empire that includes a rehearsal space, a mail

order and instrument manufacturing business, and a musical-equipment rental service.

All of which arose from the typical drummer’s complaint; having to lug carloads of equipment for the same paycheck as a less-burdened flute or guitar player. “I’m a musician, not a truck driver,” Toperzer scoffs.

In the ’50s, Toperzer was one of the busiest drummers in town, working hotel one-nighters with dance bands and orchestras nearly every evening—this after putting in a full shift as a public-school music teacher. The grind took a toll. “I don’t show up three hours early and leave three hours late for the same money as somebody who walks in with a fiddle, or a piano player who walks in with nothing,” declares the drummer, a trace of aggravation in his voice even now.

So Toperzer had the audacity to

demand that promoters not only pay him for showing up, but shell out an additional rental fee for his station

wagon full of gear. Surprisingly, it worked—to the point where Toperzer was soon contracting out equipment for

other musicians. He quickly found himself with a house full of musical tools and a burgeoning rental business.

He opened the retail shop partly to store his clattering collection. Eventually, he quit teaching, believing

that he could have more impact providing materials to educators than teaching tots where the one-beat is.

So Toperzer had the audacity to

demand that promoters not only pay him for showing up, but shell out an additional rental fee for his station

wagon full of gear. Surprisingly, it worked—to the point where Toperzer was soon contracting out equipment for

other musicians. He quickly found himself with a house full of musical tools and a burgeoning rental business.

He opened the retail shop partly to store his clattering collection. Eventually, he quit teaching, believing

that he could have more impact providing materials to educators than teaching tots where the one-beat is.

Still, Toperzer retains something of a professorial air. Offering advice, criticism, support, and strong opinion in his lilting Boston brogue, he clearly enjoys engaging all who enter his store in hardy debate—and not merely about percussion. You may think you just stopped in to pick up a new pair of drumsticks, but if he senses you’re a bright student, Toperzer will hit you with a pop quiz. (Example: What’s the difference between a piano and an organ? You play a piano, you operate an organ.

As philosophical as Toperzer can become, he is surprisingly dispassionate when discussing the mainstay of his business. “A drum is a drum is a drum,” he says with indifference. “It goes boom boom. If it doesn’t, you’re in trouble. If it does and you can’t play it, you’re in trouble. Otherwise, it goes boom boom boom.”

Of course, Toperzer is not entirely

without sentiment. He points out an old red bass drum. “I bought that for $5 in 1945. At that time, it was about

40 years old. It was built by George Stone,” he says. Stone is one of the seminal figures in modern percussion,

a drum maker and teacher whose books are still in use. “It’s a wonderful, wonderful drum,” he says affectionately.

“The drum next to it is almost 100 years old,” he continues, indicating a scruffy wooden bass drum. “And they’re

still working. I got my five bucks back a couple of times.”

Of course, Toperzer is not entirely

without sentiment. He points out an old red bass drum. “I bought that for $5 in 1945. At that time, it was about

40 years old. It was built by George Stone,” he says. Stone is one of the seminal figures in modern percussion,

a drum maker and teacher whose books are still in use. “It’s a wonderful, wonderful drum,” he says affectionately.

“The drum next to it is almost 100 years old,” he continues, indicating a scruffy wooden bass drum. “And they’re

still working. I got my five bucks back a couple of times.”

Toperzer speculates that his old-time beater might have been used in John Philip Sousa’s band. “And of course that music is still played and that drum sounds like the drum should sound.”

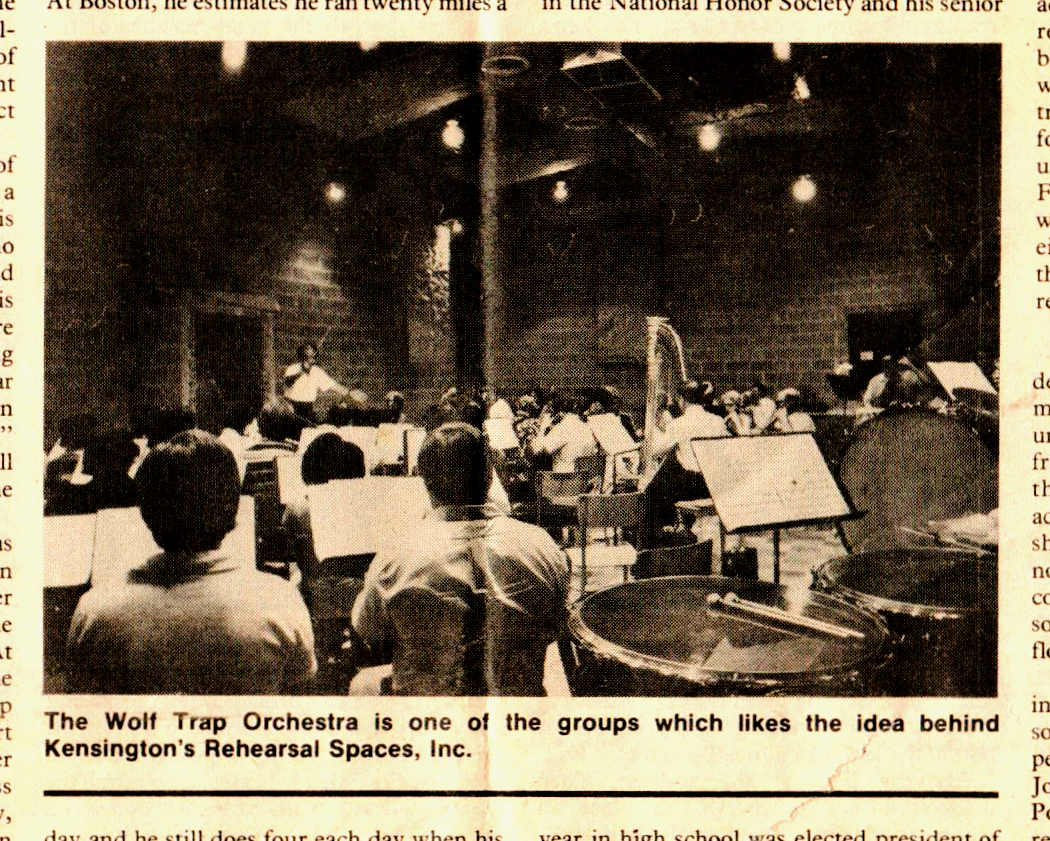

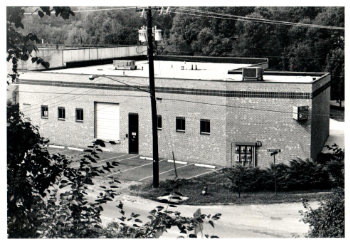

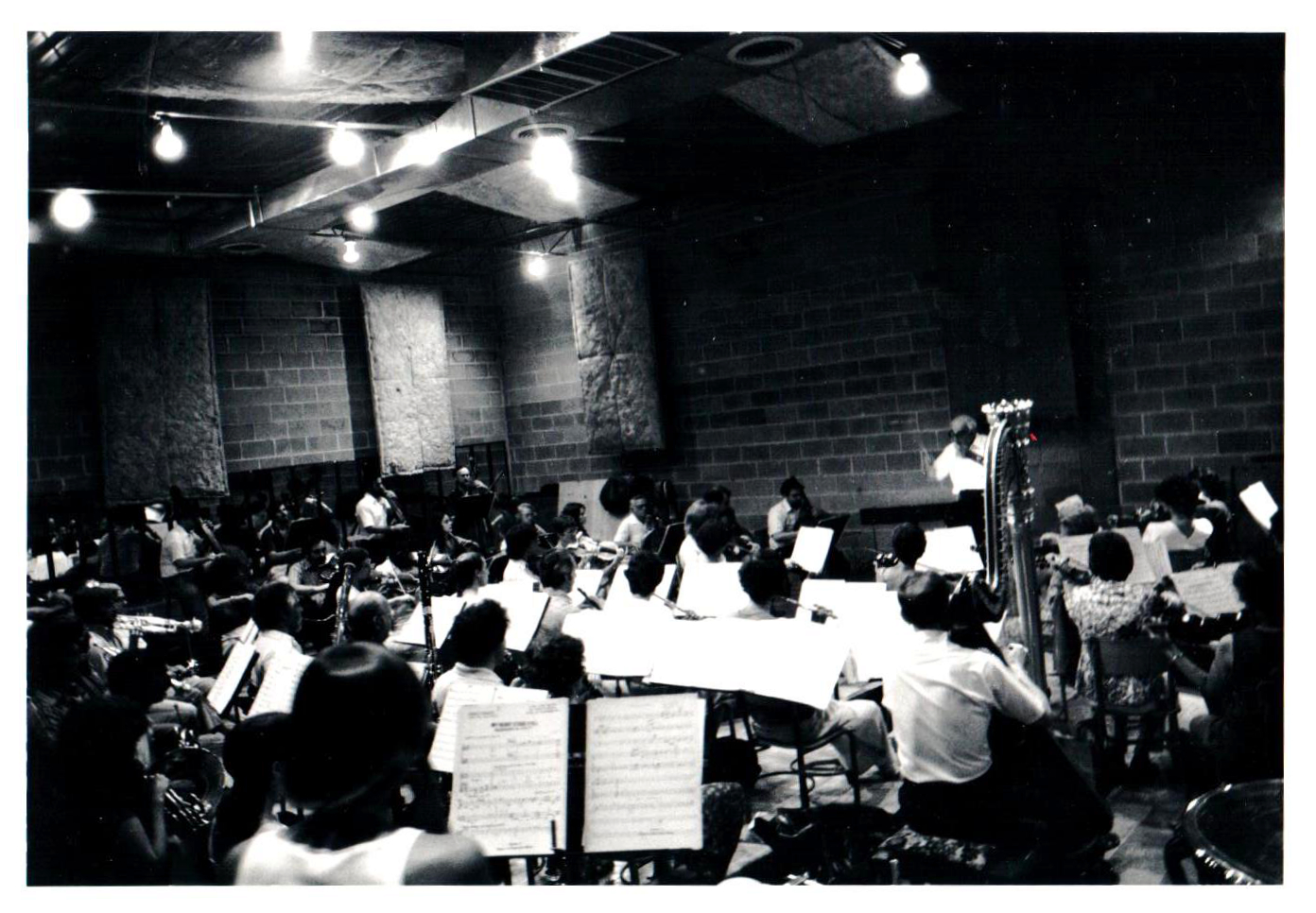

Toperzer dispenses these heresies and verities from the Kensington warehouse/headquarters of Rehearsal Spaces and Professional Rental Services, the Drums Unlimited subsidiary run by his son, Michael. Conversation vies with the constant sound of musical instruments being tested and loaded onto one of five trucks that deliver them to such disparate places as Georgia theme parks, Atlantic City casinos, and the stages of Wolf Trap and the Kennedy Center. The clanging concerto of chimes, drums, bass, piano, and electric drills and sanders provides a suitably percussive background.

But we don’t spend much time talking

the usual drum talk—Buddy vs. Gene, Ludwig vs. Yamaha, blah blah blah. We talk of history, discipline, and the

cycles of nature. In explaining the complexities of sending musical instruments around the world, Toperzer

mentions the half-dozen sets of tuned automobile horns that he supplies to orchestras intent on correctly

playing Gershwin’s “An American in Paris.”

But we don’t spend much time talking

the usual drum talk—Buddy vs. Gene, Ludwig vs. Yamaha, blah blah blah. We talk of history, discipline, and the

cycles of nature. In explaining the complexities of sending musical instruments around the world, Toperzer

mentions the half-dozen sets of tuned automobile horns that he supplies to orchestras intent on correctly

playing Gershwin’s “An American in Paris.”

But to fully explain how one tunes automobile horns, Toperzer must first go back to the 1890s and the celeste, which, he points out, did not exist until Tchaikovsky heard it in his head and thought it might be nice for “The Nutcracker Suite.” “Somebody had to invent what he heard,” Toperzer says, beginning a story about the composer traveling to France to find a man who could build his imaginary device. “George Gershwin heard these taxi horns in Paris and found a guy in Germany who made things like foghorns and sirens.” He pauses slightly, knowing he has a good punch line. “And that man still makes them,” he says, before adding with a grin: “He’s hard to find.”

Not content to pick up the usual

catalogs and order the usual soundmaking machinery, Toperzer acquired some of his inventory by roaming through

Europe “finding lots of these fellows”—ancient artisans including “the man who tunes cowbells. And the man who

makes the cowbells that the other man tunes,” he says. “The cowbells are made on an island in Bavaria. And a

man 200 miles away goes to this island and goes through bins of these Swiss cowbells, and finds things that

are close to a note. And he collects these and he puts them in his van and he goes back to Germany. And they

have a little shop there and stroboscopes, and they bring these into tune by cutting them and reshaping them

and so forth and so on.”

Not content to pick up the usual

catalogs and order the usual soundmaking machinery, Toperzer acquired some of his inventory by roaming through

Europe “finding lots of these fellows”—ancient artisans including “the man who tunes cowbells. And the man who

makes the cowbells that the other man tunes,” he says. “The cowbells are made on an island in Bavaria. And a

man 200 miles away goes to this island and goes through bins of these Swiss cowbells, and finds things that

are close to a note. And he collects these and he puts them in his van and he goes back to Germany. And they

have a little shop there and stroboscopes, and they bring these into tune by cutting them and reshaping them

and so forth and so on.”

Simple. But Toperzer’s Indiana Jones-style adventures cover the percussive gamut. Though the more reliable plastic drum head has been the norm since the late ’50s, there are, says Toperzer, “purists out there who want calfskin or goatskin or monkey skin or snakeskin—or sturgeon skin even, which the Egyptians use—on different kinds of ethnic drums. And so we’ve had to find sources for these things.”

“It’s not just a primitive catch-as-catch-can,” he asserts, maintaining that there is a skill and an art to both the making and the buying of musical exotica. He adds, almost sadly, “I never did find a safe source for fish skin that wasn’t rotten.”

In an age of digital sampling, where anybody can be an “artist” with the push of a button, this sort of insistence upon authenticity is refreshing. It also goes a long way toward explaining why that small sign in Bethesda is still beckoning after all these years. Another example: When Modern Drummer magazine published a list of “The 25 Best Drum Books,” all 25 could be found on Toperzer’s shelves, a fact the former educator is proud to announce.

These days, the globe-trotting is left mostly to his inventory. And as he has backed up the likes of Billy Eckstine, Tony Bennett, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Peggy Lee, and Julie Andrews, you won’t find this sixtysomething stickman pounding out a fox trot at some wedding. But the lure of the traps remains.

Toperzer mentions a recent party where he ascended to the drum throne. “A number of wonderful players were there,” he says, including Ray Bryant and bassist Keter Betts. His face brightens as he remembers the fun. “Except Keter and I were exhausted. There were three piano players. They each played an hour nonstop, showing everything they could do. And we played for all of them.” He laughs softy. “That kind of thing is wonderful for me.”

Of course, he still had to set up all those drums himself. —DAVE NUTTYCOMBE

The legacy Continues

Working side by side with Mickey, Michael Toperzer not only supported his fathers vision but expaneded it. Michael realized the vision of adding a Rehearsl Space to their line up. Washington DC was in need of a Professional environment for working musicians, and Michael knew just what they needed, and built it from the ground up, literally. Eventually Michael would go on to lead the company in all aspects and continue to expand while keeping the personal touch and relationship building that was started with his father.

JEFFREY BUTLAND FAMILY-OWNED SMALL BUSINESS OF THE YEAR 2009

F. MICHAEL TOPERZER III President FMT, Inc. T/Drum Unlimited Rentals